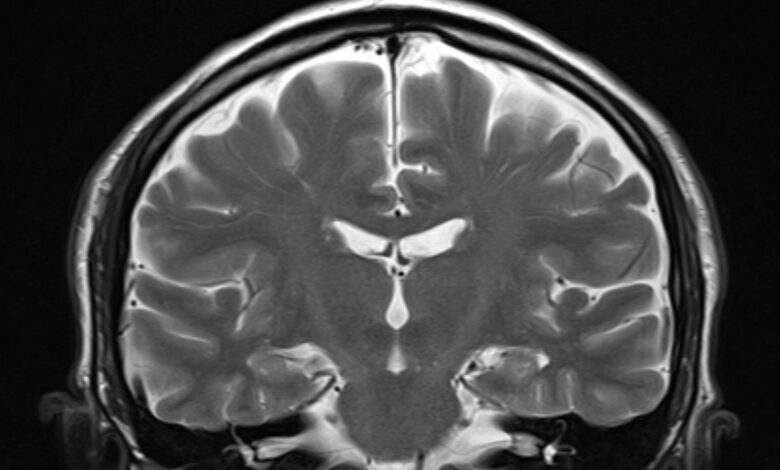

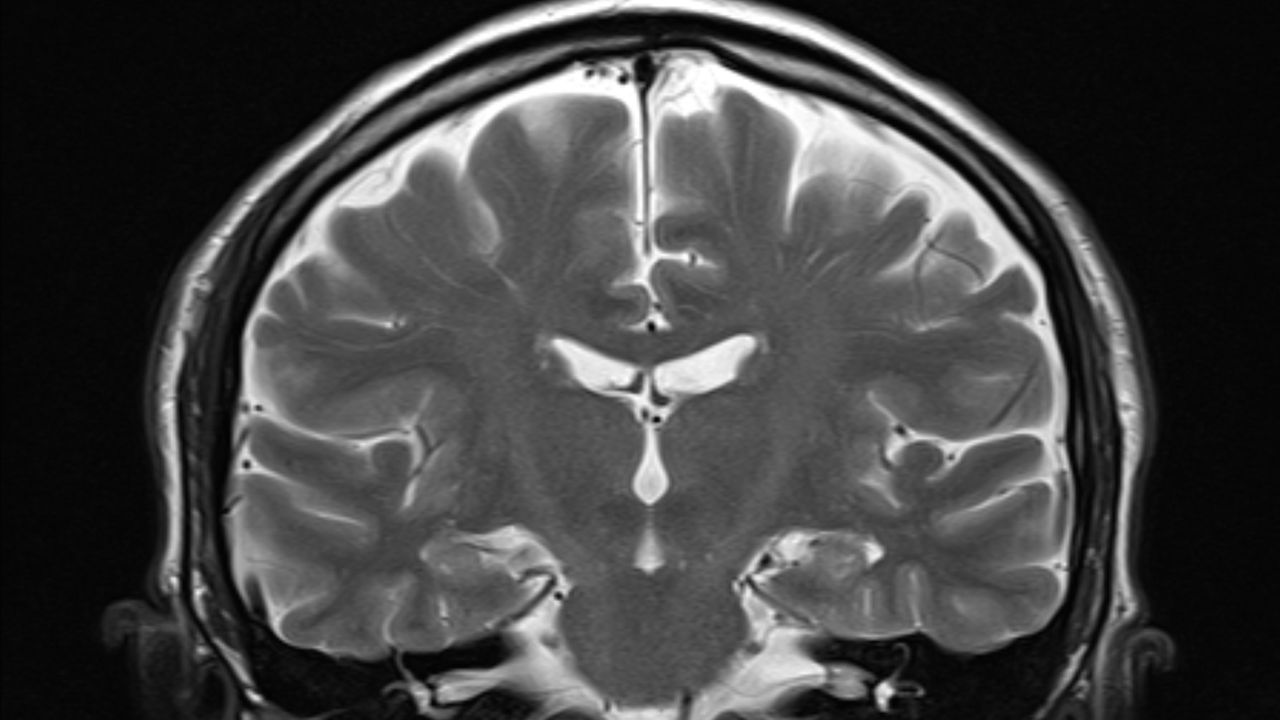

A single MRI can reveal how quickly you’re aging, scientists claim

Scientists can now judge how fast your whole body is aging based on a single snapshot of your brain, researchers claim in a new study.

The scientists, who published their findings July 1 in the journal Nature Aging, have developed a benchmark of biological aging based on brain MRIs. The team says the tool can predict an individual’s future risk of cognitive impairment and dementia, chronic conditions like heart disease, physical frailty and early death.

“Our paper presents a new way of measuring how fast a person is aging at any given moment using the information available in a single brain MRI,” said first author Ahmad Hariri, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. “Faster aging increases our risk for many diseases including diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and dementia,” he told Live Science in an email.

Hariri and colleagues used data from the Dunedin Study, which followed 1,037 people from Dunedin, New Zealand, from birth to middle age. These participants, born in 1972 and 1973, periodically received 19 assessments to check the function of their heart, brain, liver, kidneys and more.

To develop their tool, the team analyzed the brain MRIs taken from this cohort at age 45 and ran the data about brain structure — the volume and thickness of various brain regions and the ratio of white to gray matter — through a machine learning algorithm.

They compared the processed brain data to other data collected from the participants at the same time, such as tests of physical and cognitive decline, subjective health statuses, and signs of facial aging, like wrinkles. They asserted that bigger declines in those areas were tied to a faster pace of aging, overall, and then correlated features of the brain data to those metrics. They called their resulting model “Dunedin Pace of Aging Calculated from Neuroimaging,” or DunedinPACNI.

Related: Epigenetics linked to the maximum life spans of mammals

Previously, the team created a similar tool called Dunedin Pace of Aging Calculated from the Epigenome (DunedinPACE). That metric looked at methylation — chemical tags that attach to DNA molecules — in blood samples to estimate people’s pace of aging. Methylation is a type of “epigenetic change,” meaning it alters genes activity without changing DNA’s underlying code.

“[DunedinPACE] has been widely adopted by studies with available epigenetic data,” Hariri said. “DunedinPACNI now allows studies without epigenetic data but with brain MRI to measure accelerated aging.” The researchers directly compared DunedinPACNI to DunedinPACE, finding that they generated similar results.

To see if their new tool could be useful beyond Dunedin, the team used it to estimate the pace of aging using MRIs in other datasets: 42,000 MRIs from the U.K. Biobank; over 1,700 MRIs from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI); and 369 from the BrainLat set, which includes data from five South American countries.

“Making sure our findings generalize across datasets and demographic groups is a big priority for brain imaging research,” study co-author Ethan Whitman, a doctoral student at Duke, told Live Science in an email.

They found that DunedinPACNI could also estimate the rate of aging in these other cohorts, and that it did so as accurately as other measures used in the past.

The U.K. Biobank and ADNI also include measures of specific health effects of aging, including tests of physical frailty, like grip strength and walking speed, as well as rates of heart attack, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and death from all causes within the cohorts. Using these additional measures, the team was able to link faster aging rates, as determined with DunedinPACNI, with increased risks of heart attack, stroke, COPD and death.

Hariri believes DunedinPACNI has the potential to be widely adopted because the type of MRIs it uses are routinely collected. Now it’s a matter of crunching the data and determining standards of what reflects “healthy” and “poor” aging, he said.

“The fact that it worked well with the BrainLat data is a big win for the investigators because it supports the generalizability of the model,” said Dr. Dan Henderson, a primary care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School who was not involved with the study. “It would still be worth looking at other data sets where genetic and other factors might be different in important ways,” he added.

Henderson said he could see DunedinPACNI eventually being used in place of conventional health measures to fine-tune medical interventions for individual patients. Whitman also sees broad implications for the research. Assuming it’s validated for use by doctors, he thinks it could help patients prepare for age-related health issues before they manifest.

“We were really amazed that our tool was able to predict disease risk before symptoms had started,” Whitman told Live Science in an email. “We think this is a great example of why it’s important to study aging in general, but especially in younger, healthy people. If you only study people after they have gotten sick, you’re missing a lot of the story.”

Brain quiz: Test your knowledge of the most complex organ in the body

Source link