Even brief exposure to air pollution can push the placenta into an inflammatory state, lab study suggests

Even brief exposure to air pollution may alter the structure of the placenta and push the organ into an inflammatory state, recent laboratory research finds.

Scientists already knew that particles found in air pollution can reach the placenta and get taken up by immune cells there.

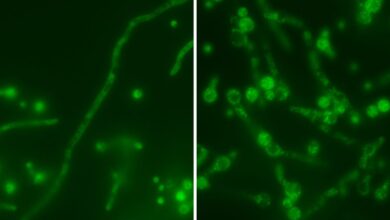

The new work added to this understanding by zooming in on special immune cells of the placenta — called Hofbauer cells — to see how their function changed after they were exposed to compounds found in real air pollution.

“I think that this is an important step in filling in the gap between what we know from epidemiological studies,” Grigg said.

Those studies pointed to links between exposure to pollutants during pregnancy and the risk of the blood-pressure disorder preeclampsia, for instance. Preeclampsia is tied to poor blood flow to the placenta, and thus low oxygen in the organ. Some researchers argue that placental dysfunction is the root of preeclampsia, but not everyone agrees, as some point instead to the maternal cardiovascular system. But nonetheless, the placenta is thought to be a key factor in the disease.

The recent research, published online in March in the Journal of Environmental Sciences, will also run in the journal’s February 2026 print issue. It used what’s known as “ex vivo dual placental perfusion,” which means the scientists collected full-term placentas from volunteers who donated them at the time of birth, either via cesarean section or vaginal delivery. In all, 13 healthy placentas were donated.

Related: Lab-grown mini-placentas reveal clue to why pregnancy complications happen

“You can’t really expose women to air pollution as an experiment,” study co-author Dr. Stefan Hansson, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and a senior consultant in obstetrics at Lund University in Sweden, told Live Science. “So the best model, then, is the placenta perfusion system that we used.”

After birth, the placentas are connected to an artificial perfusion system that mimics elements of the female reproductive system. “Within 30 minutes, you hook it up in an artificial womb and uterus,” Hansson explained. Tubes connected to one side of the placenta represent the maternal circulatory system, while tubes on the other stand in for the umbilical cord that would connect to the fetus.

Tubes feed nutrients and oxygen to the placentas, keeping them healthy for about six hours and mimicking both the maternal and fetal sides of the organ. Meanwhile, scientists can monitor the organ’s metabolism, homeostasis, blood-pressure levels and the behavior of its immune cells.

“That’s a good thing in the sense it’s covering perhaps the more complex interactions between cells, how fluid and particles are moving through cells,” Grigg said. By comparison, studying individual placental cells in a lab dish is arguably less realistic.

The researchers then introduced air pollutants into the system to see what happened. Six placentas were left unexposed to pollution, to serve as a comparison; five were exposed to pollution for five hours; one was exposed for 60 minutes; and one was exposed for 30 minutes. Tissues and fluids were sampled from the system before, during and after these perfusions.

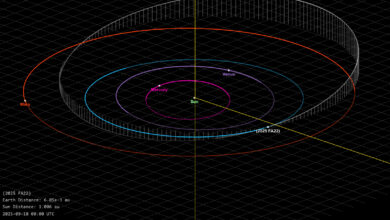

The pollutants themselves were drawn from a previous sampling of air pollution in Malmö, Sweden taken in spring 2017. The samples were collected at a street crossing that sees an annual average traffic density of about 28,000 vehicles. The team focused on “fine” particulate matter, or PM2.5, which includes particles smaller than 2.5 micrometers.

On that point, Grigg told Live Science that “the concentrations of particles that they’re using in the perfusates are almost certainly very much higher than the very small concentrations that are going around the body,” based on previous research. So there’s a question about whether the doses they’ve tested closely reflect real life. “I think that’s probably a valid limitation for this,” he said.

Related: Canada’s 2023 wildfires contributed to 87,000 early deaths worldwide, study estimates

Nonetheless, at the concentrations tested, the pollutants had a clear effect on the placentas. Even when exposed for only 30 minutes, the placentas showed distinct changes in their collagen, a structural protein that helps organize the tissue. The collagen appeared looser and “disrupted” compared with the dense, organized collagen of the unexposed tissues.

The team also noted that, after an hour of exposure, the placentas started making more human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), a hormone that peaks in the first trimester and helps maintain the uterine lining. However, high levels of the hormone in the second trimester have been tied to a higher risk of preeclampsia, studies suggest. The new study hints that air pollution may be a factor that drives up hCG levels, though that idea needs to be confirmed.

Meanwhile, the Hofbauer cells of the exposed placentas had a “visible activated appearance” and had shifted into an inflammatory state. In a healthy placenta, the cells are typically biased toward an anti-inflammatory state, but in the context of preeclampsia, they tend to shift in the other direction, the researchers noted in their report.

“This is, of course, an artificial setup and you’re exposed for a couple of hours,” Hansson noted. You can extrapolate and assume that, in a full-term pregnancy, these harmful effects might accumulate, he said. But as it stands, the placental perfusion system can’t directly capture the effects of such long-term exposure, and it also looks only at full-term placentas, not at those in earlier stages of development.

It stands to reason, though, that “if it’s happening all the time, then that’s going to be clinically relevant,” Grigg said.

The results hint that if the inflammation driven by the Hofbauer cells could be subdued with a drug, that may help ward off one factor contributing to preeclampsia in polluted areas, Hansson suggested. That idea remains to be tested in trials, though, and inflammation isn’t the only feature of preeclampsia.

What’s more, a more effective intervention would be to reduce particulate matter in the air, Grigg said. “We should be reducing exposure to PM2.5; you don’t need any more information about that [to justify taking action],” he said.

Grigg also cautioned that the new results don’t necessarily point to precautions that individual pregnant people should take.

“I sort of hesitate to say, ‘Well, pregnant women have to do something different to protect themselves,'” he said. “There are enough things that pregnant women have to do rather than thinking about how they move around the city.”

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Source link